The Bizarre Reason You Make Bad Choices

Your Future is Foreign to You

Oh my God, I’m never drinking again.

-Almost anyone who’s ever been to a party.

Most of us who enjoy a drink or two from time-to-time have, on occasion, found ourselves more than just one or two deep—sometimes considerably more—to great regret the following morning. Finding oneself in that unfortunate condition, trembling hands massaging clammy forehead, most have muttered, “I’ll never drink again.” Usually these utterances are not quit audible, just shy of a whisper. Which is a good thing, as it leaves no witness to hold them to account on the next occasion that ‘just a few more’ seems like a great idea. And usually there is a next time.

This happens to people who drink frequently and to those who rarely imbibe. Nearly everyone who enjoys alcohol, from the hardcore alcoholic to the truly “social” drinker, understands that at some point in the future circumstances will be such that they will overindulge and wake up uncomfortable. And perhaps most notably, they will be racked with regret over their choices the prior night. This is extraordinary because they’ve experienced this same regret previously. The script has played out before. The night-time version of you prioritized the fun of the moment over the morning version’s comfort.

In general these sorts of trade offs are perfectly normal. All decisions have consequences, and when deciding between courses of action the value of the different outcomes are weighed against each other. We can’t have it all. A luxurious and delicious dinner may be packed with more calories than you might otherwise find acceptable if not balanced against the particular delight of the meal. An expensive vacation, while not in line with long-term financial goals, may be judged ‘worth it’ because of the memories made with loved ones.

But the example of a night of uninhibited drinking and next-day repercussions seems different from most trade-offs we make. If I choose a financially ill-advised trip, after I return I can at least bask in the recollection of good times while dealing with the fall-out. But if I drink to excess I might not even remember the fun I had the night before. The night-me made the decision, and reaps the benefits, while the next-morning-me exclusively suffers the consequences.

And those consequences can be significant (I’ve seen them—remember, I’ve worked in an ER for over ten years). They can range from ‘just’ a hangover to significant legal, financial, health, and relationship problems stemming from alcohol-induced poor decision making. Witnessing the regret of a newly sober patient over the damage done by their intoxicated self the night before can be heartbreaking. Sometimes they’ve done damage that permanently alters the course of their life. All because of decisions they often don’t even remember making. Facing ramifications (even if just a headache) of decisions that aren’t even recalled gallingly highlights the power imbalance between the past and present versions of oneself. It’s hard not to feel like being subject to the whims of another person entirely.

In a way it’s surprising this ever happens more than once. First time night-you may be ignorant of what the morning brings. But the next time the same decision is made, some-other-night-you has the full knowledge of what next-morning-you will suffer—because they suffered it. What gives? I know what you’re thinking. It’s the obvious answer. And, I think, the correct one. Gonna-have-fun-tonight-you doesn’t set out planning to drink too much and do dumb stuff. But after the disinhibiting effects of the first drink or two kicks in, they’re much less concerned with how did-I-do-that-again-last-night-you will feel in the morning. All of a sudden the knowledge that hangovers suck doesn’t seem so important.

So, if there’s such a straightforward explanation (the effects of alcohol on the brain), why bother discuss it? My first point is to evoke the vividness of personal experience. Most adults have had at least one morning steeped in misery because of the sauce.

My second objective with the drinking example, thanks to alcohol’s ability to cloud memory, is to highlight the curious way that time affects how we make choices. Our decisions are largely based on when we will feel the consequences of our actions, not on the real value of those consequences—positive or negative. We treat our future selves, who will experience the consequences of our actions, as if they were someone else entirely (someone we may not even like given how miserable we are willing to make them). In the case of alcohol, where the future morning-you may not even remember what last-night-you did, that feels intuitively true. Alcohol, when overindulged in, functions like liquid Severance.

For those not in the know, Severance is a pretty great show made by Apple. The main plot device is that the characters have undergone a surgical procedure called ‘Severance’ which renders them unable to remember any of their outside life while at work. The reverse is also true, at home they have no idea what their work involves.

The ability of booze to separate us from an earlier version of ourselves (at least for a few hours) in both awareness and identity is unique to the chemical properties of ETOH. But it highlights something fundamental about how our brains work. It’s the chemical exception that proves the rule. Because it turns out our brains do something like this all the time. Which explains some of why we find it so hard to make those choices where the positive results are only realized in the future.

The brain, as 3 pound wads of jelly go, is pretty self-involved. This is no big surprise, let’s be honest, most people are pretty self-involved. But the brain takes it to a whole other level. Now I’m not criticizing the brain here. It’s got a big job, driving a human around and calling the shots to get that person through their day intact is no joke. This responsibility obviously requires pretty serious self-focus. The brain’s habit of paying close attention to oneself makes even more sense when you consider that the modern human brain hasn’t changed for tens of thousands of years. It evolved in a time when every day was a struggle for survival. Bad choices had more significant consequences than a miserable morning. In fact, bad choices tended to prevent you from making any choices ever again. So it makes sense that the brain, which developed in a much less forgiving world than we live in now, is all about itself. It was literally made to ensure our moment-to-moment survival. But everything in life is a tradeoff. And while the brain’s relentless focus on the self in the present served us well during our evolutionary history, it presents us with some difficulties and surprises today.

The brain always knows who it is, but it loses sight of who it was and is partly blind to who it will be. Past and future may not matter much in a prehistoric world of daily and immediate threats. In that setting surviving is thriving. But in the modern world (at least in the developed world) our daily survival is all but guaranteed, and how we thrive is the result of actions taken, and not taken, over years. In the current environment a strong concept of the future-self is important for making choices that culminate over years. Unfortunately, to the brain the future-self is a stranger.

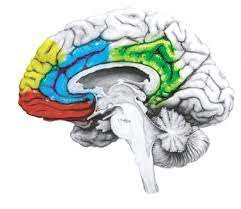

Functional magnetic resonance imagine (fMRI) allows researchers to examine which parts of the brain are more active during certain cognitive processes by tracking blood flow. Translation: We can scan your head while you’re thinking about certain things and looking to see where all the work is being done.

Certain areas of the brain, collectively referred to as cortical midline structures (CMS), activate when research subjects think about both themselves and other people.

But they don’t light up equally. They turn on more powerfully and in different patterns when thinking about oneself than someone else. This is not surprising. As we’ve discussed, the brain’s job involves paying close attention to what you’re doing to make sure you don’t screw anything up. It wouldn’t do to step into traffic or make a grievous faux pas at work. It’s thought that the neural circuits in the CMS serve to locate information on a spectrum of connection and importance to the self. Studies show CMS activity is directly related to self-relevance. Its activity increases linearly with increasing relation to the self.

OK, nothing too crazy so far… Here’s the curveball.

When you think about yourself in the past, the brain looks like you’re thinking about a stranger. The pattern of CMS activation, the brain circuitry that’s turned on, treats your past-self as a different person from who you are today. You may ask—so what? After all, don’t we frequently use the language of change about ourselves? I’m sure you’ve heard someone express the notion that, “I’m not the person I was.” This study suggests it’s more than a turn of phrase, it implies that the the physical process of thinking involves Severance between past and present. You may ‘know’ that you are the same person you were a year ago, but at the hardware level your brain treats them as different. There is you, who exists now, and there was… someone else.

If that’s where it stopped, I might shrug my shoulders. The past is, after all, past. And your prior-self is actually gone forever, living on only in how its actions and experiences helped mold your current-self. Perhaps there’s no significance to this feature of how our brains process our past, and it’s just how the mental filing cabinet works. I can even image a just-so explanation. For instance, thinking about our past in the same way we think about our present could subject us to excessive rumination and regret. In this case, placing the past-self in the mental category of ‘other’ may keep us focused on the present, where we take the actions that create our futures.

And that’s what it’s all about, right? The future. The only action we can ever take is now, in the present, but the impact of that action spreads across our futures. It seems natural that our mental focus and sense of self should reside where our actions matter and their impact felt, now and into the future.

Only it doesn’t…

Like the reveler with a few drinks under their belt who loses sight of how they’ll feel in the morning, your future-self is a stranger to you. We’ve talked about delayed discounting before, the way in which people value things less the farther away in time they are. This phenomenon underscores why it’s so hard to make decisions and take (sometimes difficult) actions that benefit you only in the future. But it’s not just a behavioral pattern observed by psychologists. Your brain, as reflected in CMS activation patterns, treats thinking about yourself in the future the same way it treats thinking about yourself in the past. Like someone else. A brain that treats the future-self as an ‘other’ seems poorly equipped to make choices in your future’s best interests.

In pursuit of living a long, healthy, vibrant, and financially secure life this appears to be a debilitating deficit—though from an evolutionary point of view, given the importance of attention to the immediate for our ancestors, an understandable one. It certainly plagues many who would like to live their lives differently, yet find themselves unable. But like all things human, it varies. And the variance may show a way out of the trap.

Everyone engages in some degree of delay discounting. We all value things now more than in the future. But not everyone does it to the same degree. That should be obvious. We all know people who save scrupulously for the future at the expense of current pleasures, while on the other hand we’ve encountered those who can’t seem to think a day ahead and seem to spend every dollar they have. This behavioral variation isn’t random. The degree to which someone devalues things in their future is directly related to how strongly that person feels connected to their future-self. That seems intuitive, if I’m more connected to my future-self I’m more likely to take that person into consideration with my choices.

But it’s not just a matter of how you feel, it’s how the brain works. Research subjects with lower rates of discounting (devaluing) future outcomes have stronger self-identification with their future-selves. AND under fMRI scanning their brains look similar when thinking about both their future and current-selves. While the brains of research subjects who don’t feel connected to their future-selves and who devalue the future more strongly look like they are thinking about someone else when thinking about their own future.

I started this project to explore the science around why we don’t make good choices that benefit us over time and what we can do to make better choices. This explains some of the why and opens the door to how we can do better for ourselves. People who are connected to their future-self have brains that work differently, they process the future-self more like the right-now-self. Not surprisingly, these people act in ways that takes the well-being of their future-self into consideration.

This is what we should all want for ourselves. Who we are and our current circumstances are the result of the choices we made in the past. Our choices today make our futures. We have all looked back and regretted certain choices. We would have less occasion for regret if we made decisions with greater consideration for who we want to be in the future and what we want our lives to look like.

To move things in this direction, the lever to push on appears to be the connection to ones future-self. Building a stronger connection and a deeper sense of identification with the person you will become could be a powerful tool in helping you change your direction, navigate your future, and cultivating the life that you want.

- TheTimeDoc