A Beginner’s Guide To Time Travel

To understand why making changes is so hard, imagine something impossible

I’d like you to try something unusual. Try to imagine a new color. Yeah, you heard that right, a new color. I’m not talking about an extra bright green, or an orangier yellow than whatever yellow thing you’re looking at. I’m talking a whole new color. Brand new, never seen before. Go ahead, give it a try. Take all the time you want.

So… didn’t go too well, did it? It doesn’t seem like it should be that hard in principle. Our eyes are pretty amazing. They only register a narrow band of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum, visible light. But there’s nothing that says it has to be exactly that way. It’s not too much of a stretch to suppose the proteins sitting on our retinas could be just a tad different. An amino acid tweak here and there, giving them the ability to recognize a broader EM range. You can imagine some CRISPR equipped mad scientist making that happen.

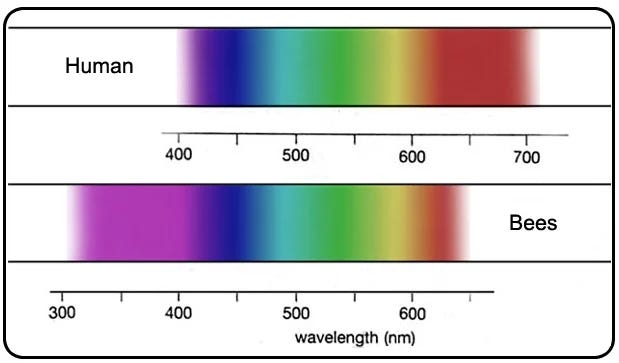

You don’t even have to imagine too hard. As it turns out, not all visual systems perceive the same wavelengths. Bees, for example, can’t see the reds tones that we do, but are able to detect into the ultraviolet range that’s invisible to you and I.

If you could see in that range, what would it look like? Extra purply purple? A violetness beyond violet? Well, no. Those are just colors that you can already see. When you try to imagine (which is really to ask you to simulate the experience of) a wholly new color, you run into a wall. The brain just can’t do it. You’d have better luck working on your dance moves and asking a bee.

The point of this exercise is to illustrate the impossibility of conceiving the experience of something we are not built to perceive. We can describe the wavelength of ultraviolet light and understand it as an abstraction or analogy, but we can’t experience it as a color. That particular electromagnetic frequency is outside the realm of our sensory experience, and consequently we can’t really imagine the sensation of seeing ultraviolet. It is, quite literally, inconceivable to us.

Conversely, other things are so deeply ingrained and hardwired into our perception that imagining either their absence or a different experience of them is equally unthinkable. Our intuitive, gut-level understanding of the world is bounded by how we experience it. Our perceptions structure our understanding in ways that are hard to recognize from the inside.

Edge cases, where something is broken, can help us glimpse outside of this box. Take something as fundamental as motion. It’s such a basic part of how we interact with the world that I struggle to imagine its absence. What would it even mean to experience the world without motion? Trying to picture it amounts to little more than my conjuring up a series of mental still-frames. Which I suppose is fairly accurate when everything is staying put. But what happens when someone stands up? Or a dog chases a squirrel? My brain hurts a little even attempting it.

Despite my difficulty, it turns out an unlucky few are broken in just the right way so as to make this their reality. A neurologic condition, Akinetopsia, also known as “motion blindness”, renders sufferers unable to perceive motion. A mild form can be induced by medication, while a more severe version can be caused by stroke, trauma, Alzheimer’s, and other brain lesions. It is exceedingly rare, with only a handful of documented cases (I’ve certainly never seen it in the ER). It’s also extremely debilitating. Simple tasks like pouring coffee are challenging because the liquid appears frozen. The victim of this malady is unsure when to stop pouring, as they cannot perceive the movement of the fluid rising. Some such afflicted are able to see stationary objects, which then disappear when they move, only to reappear again when they are still. Others find crossing the street a harrowing experience as they can see cars but not their motion—is that truck stopped and waiting for pedestrians to cross or barreling though the intersection without heed?

Knowing about this condition doesn’t allow me to truly understand what these few unfortunates are subjected to. I can’t imagine it in perfect fidelity. I’m still limited to picturing still scenes, but now with objects and people appearing and disappearing, popping from one place to another. But perfect fidelity isn’t the point. The point is to crack the door and give me a glimpse. It’s a glimpse of something that I can never fully understand, but it’s also something I wouldn’t otherwise consider. I won’t ever experience what they do, but knowing about Akinetopsia gives me a hint of of a way of experiencing the world that my brain is simply incapable of.

The relevance of all this, bee vision and motion blindness, is how they illustrate constraints on our intuitive understanding of the world. We can only experientially know the things that we are built perceive (we can’t imagine colors we can’t see). And our experience is dictated by how our brains process sensory inputs (lacking a specific brain lesion you necessarily see motion—and can’t really imagine its absence). We are constructed to understand the world in very specific ways. It’s part of what makes us the very specific thing that we are—human.

Recognizing this opens the door to considering different ways in which the world could be experienced. Like trying to picture a new color, we can’t exactly see them or truly feel them with our minds. But while the details of these alternative perceptions may be out of our grasp, perhaps we can get a feel for the negative space they occupy. So that we might at least recognize certain deficits in our experience, perception, and cognition.

This brings me back, full circle, to the title of this post. You are a time traveler. We’re all time travelers. We just aren’t very good at it—we stink at it because we have no control over our journey. We can affect neither the direction nor the speed of our travel. We go in one direction, at one velocity. But we don’t really notice the trip. We realize time has passed in hindsight. We look back and realize we are not where we were and in some regards we aren’t even the same person anymore. We are like an unfortunate with motion blindness who looks out of the train window and sees that they are in one place, and then another, but without any sensation of movement between the two locales. We are time blind.

If I wanted to give this a Greek derived scientific name, I’d call it Achronotopsia. Though I prefer “time blindness”. It’s more visceral and textured than a sterile scientific-y name. Which is important, since we’re trying to get to a gut-level understanding of something we can’t fully know. We are aware of time, but mostly we recognize its passage in retrospect. We’re terrible at gauging the passage of time in realtime (no pun intended). Just ask anyone who’s lost track of time and ended up late for something.

We’re like the motion blind person who intellectually knows they are moving, but doesn’t feel it. We know we move through time—we look around and everything is different from how it was—but we can’t feel it either. Is it any wonder that we do such a poor job navigating our way through time? The akinetopsic person overflows their cup because they cannot perceive that the coffee is rising to fill it. The time blind make choices today which lead to harmful, and sometimes ruinous, results in the future. The disconnect between the choices we make and how we feel their future consequences is responsible for a great swath of human misery. Would anyone light up. that next cigarette if they could feel themselves hurtling towards lung cancer and chemotherapy? If the the dread of fumbling with an oxygen tank and gasping for air was as palpable as the fear caused by racing down a highway at reckless speeds would more people apply the breaks to their behavior to avoid that fate? Would more people step away from the cliff edge of a poor diet if they more vividly anticipated the prize of type 2 diabetes—insulin injections, dialysis, and amputated toes and feet?

I think they would. I think our blindness to our futures, our inability to see how every day the choices we make creates those futures, prevents us from choosing a path through time that gets us where we actually want to be. We can’t select the direction or speed we travel through time, but we can pick the road we follow. There are countless possible future versions of ourselves. Who we are now is the result of the choices made by our past selves and who we will be is constantly being determined by the choices we make now. The greatest challenge in how you live your life is making choices that create the future you want, rather than the future that’s the result of the easiest and most immediately satisfying choices.

Most of us are, to some extent in the various dimensions of our lives, the result of the path of least resistance. But it’s not just that we’re too lazy to do something harder now that will benefit us more in the future. Often the thing that’s better for us over a longer time horizon is only marginally more difficult or less immediately satisfying than what, to our detriment, we actually choose. They’re not so onerous—an apple and a walk isn’t insurmountably harder than cupcake and sofa. The problem is the necessary outcomes of our behaviors, good and bad, aren’t felt at the time of choice. They not only aren’t felt, because of our time blindness, they can’t be felt. Without that gut level feel for what our choices lead to, it can be difficult to choose something just a little harder now, even if takes you to a far better future.

So where does that leave us? Hopeless resignation? Evening plans for a box of wine, bucket of fried chicken, and pack of Marlboro Reds?

Not so fast! Even though we’re blind to the passage of time as it occurs, there are things we can do to select the futures we want and increase our ability to steer towards them. You can’t intuitively navigate time, but you can use tools to get where we want to be. They’re the same sort of tools you’d use for any journey. In the next edition we’ll take a look at making the map you’ll need for your trip.

-TheTimeDoc